Sheila M. Sofian’s animated documentary films have played at festivals including Annecy, Ottawa, Hiroshima, and Zagreb among many others. Her work includes numerous short films as well as the hour-long animation/live action hybrid documentary ‘Truth Has Fallen’ (2013). She received her BFA at the Rhode Island School of Design and her MFA from the California Institute of the Arts. She is currently a Professor at the University of Southern California where she has been teaching since 2006. We interviewed Sheila about her work, and changes she has observed in the field of animated documentary over the course of her career.

CM: How did you first come to documentary filmmaking?

SS: When I was at undergraduate school at Rhode Island School of design, the degree we had there was film, video, and animation. We were required to take both film classes and animation classes. So I took documentary as well as animation there, and I loved the documentary class. And then I made my senior film, ‘Mangia!’ which I didn’t consider to be a documentary at the time although now looking back on it I have mixed feelings about that. It’s about living with an Italian family so it’s based on my experiences.

CM: It reminds me a little bit of John and Faith Hubley.

SS: I was influenced by the Hubleys, as well as Caroline Leaf and other people. So I gravitated into it, but before I did my animation degree I was studying a lot of social science and that merged a lot of my interests – the social science, documentary, and animation. And I just followed a direction that felt natural. It wasn’t really a thing at that time, so it wasn’t until later that I started hearing the words ‘documentary animation’ and that was kind of exciting because you could see that was becoming more of a reality all round the world.

CM: At that time was the work primarily considered documentary or animation?

SS: At that time it was just “animation”. There were a couple of other people that worked in non-fiction animation and we always felt kind of like second class citizens at the animation festivals because they were more interested in, you know, the craft of animation, squash and stretch, whether it looked beautiful, whereas we were concerned about content. So my films were actually performing better in regular film festivals and not in animation festivals specifically. But then over time that’s changed, there’s been more specific categories for animated documentary, and it’s been elevated a little bit more in status.

CM: And in terms of techniques that you were using, were they driven by the subject matter or driven by commissioning requirements, or other factors?

SS: I like to think it was driven my the subject matter because I think that especially when you’re dealing with memories, painting on glass works really effectively. And also for my film ‘Truth has Fallen’ – where I worked with both live action and animation – I felt that painting on glass could carry the weight of the live action more. If I cut back and forth to drawn, it would have been too dramatic of a switch. So that was one of my reasons for choosing painting on glass for that film, I felt that I could match the tone better.

CM: Was ‘Truth has Fallen’ difficult to get made?

SS: It took me a long time, it was hard to get funding, but in some ways it was good that I didn’t get as much funding as I had originally wanted. I was planning on doing more live action and I think it forced me to do more animation, which worked better in the long run. The live action was a big hurdle for me because I hadn’t worked in that way, so I had to work with a big crew of people and all the logistics that go along with that. I really wanted to push it to look more like the animation and I think I would have worked harder to do that, if I were to do it again. It was a learning experience, I learned a great deal.

CM: So actually to design the live action sequences to mimic the animation?

SS: Yes, I was trying to approach it in the same way as I approached the animation, and I was thinking of the people being more like puppets. I worked with a lot of extras and of course they wanted to be more dramatic, and act, and I was trying to control them. Animators are controlling, you know, we like to control the whole world that we’re working in. You can play God and you don’t have to worry about anything else in the frame, you can make all those decisions yourself – but with live action there are things out of your control.

CM: One of the things I find interesting in animated documentary is the tension between the dynamic spontaneity that can come with documentary, set against the tight control that an animator wants, and how that balance happens. Did you find any challenges around working with a live action crew?

SS: I was working with a professional crew of about twenty people, and I had three locations: I had the stages at USC, I had an abandoned prison, and I had a courthouse in Orange County. So there were all the logistics in terms of licensing, generators, security, catering… I had a good team of people I worked with, I had a great production manager who had a lot of experience, I had a DP that I met at a film festival and he helped me get a lot of the crew like gaffers and all that. What was great about him was that even though I was inexperienced, he would pull me aside, away from the crew and tell me how to approach things differently that I wasn’t aware of, or the etiquette on the film set. What was interesting about that film shoot was that the crew were so used to working on these horrible movies, b-movies, and they were really excited about working on something that had meaning. They weren’t used to artsy films so they would say things like “oh the artsy shots”, but then they started getting into it and making suggestions, so they were getting more and more invested in the film as time went on. So it was really a fun experience, it was a large group of people, but it was good. But I kind of prefer the solitary working alone by myself in animation, rather than having all of these variables and all of this organisation and so much to worry about with live action.

CM: And then you’re also working with interviewees?

SS: Yes that was a whole other ballgame. I got a Guggeheim Fellowship which allowed me to travel with a producer who opened doors for me, I got some good names to interview because of her, as well as my main subject for the film, who introduced me to his clients so I could interview them. We travelled all over the United States interviewing different people, and that was really fruitful.

CM: How was the film distributed?

SS: It’s hard because distributing a feature length – featurette, 1-hour film – is different from shorts. I worked through an agent and he got it on Los Angeles public library system and other public libraries around the United States where you can stream it for free, and also it’s on Amazon, as a DVD.

CM: What was the budget?

SS: The production was more than ten years, and from the inception it was more like sixteen, from the first interview that I did. And the budget was about $100k, but that doesn’t really include all of my time. I did approximately 20,000 paintings, all the animation was just me, I didn’t have anybody else help with that. But most of the money went directly to paying other people.

CM: In your work there are often political and ethical themes. Is that inherent in your work and who you are as a filmmaker, or has that come through the commissioning opportunities that there are about?

SS: None of them have come through commissioning, it’s all been work that I’m drawn towards. What excites me the most are human rights oriented films – I’m interested in making something about immigration, or a personal story. I’m really interested in ideas of good and evil because I think there’s no real such thing, I think everybody has some of both, and I’m interested in interviewing both scientists and people that have committed atrocities and learning more about that. So that’s something that sort of drives me. I think that we all tend to think of people in those terms – good or evil – but really we’re all complicated.

CM: How have your short films been funded?

SS: All grants and self-funded. It’s not that expensive for me because I’m doing all the animation myself, but music and post-production – the sound mix, compositing, that’s where the money comes in. I’ve been able to get grants here and there so that’s been very helpful. The places I’ve taught often offer faculty grants that I’ve been awarded, so that’s been helpful.

Can you talk about your most recent short film, ‘Disabled: A Love Story”

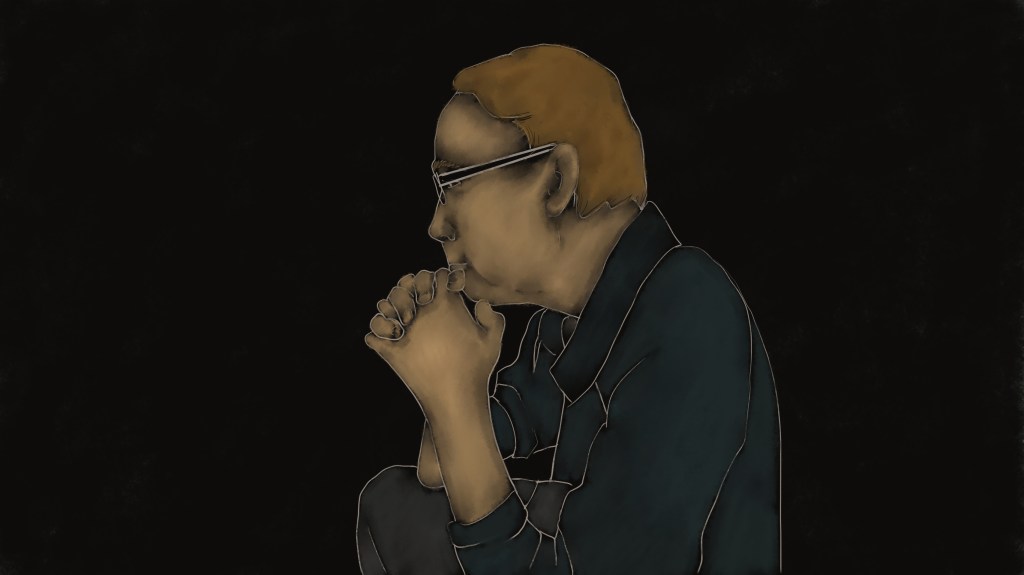

‘Disabled: A Love Story’ is an animated documentary exploring the effect multiple sclerosis (MS) has had on the lives of Terry, now a paraplegic, and her husband/caregiver, Jon. Using audio interviews and expressionistic animation, Jon and Terry describe their difficult journey. Beginning with the diagnosis and continuing through their +35-year marriage, Terry struggles to continue working as a city planner and teaching at MIT while losing her mobility. Jon works as a writer, and together they learn to adapt to each stage of the disease.

As the MS progresses, Terry grows more dependent on Jon. Despite her worsening condition, until recently Terry continued teaching. Jon’s care has made it possible for her to continue working throughout her advanced stage of MS. Jon and Terry describe the emotional and physical toll the disease has taken on them and their relationship.

The use of animation allows the audience to empathize with Terry without judging her based on her appearance. The digitally drawn animation and smeared colors create an intimate representation of Terry and Jon’s experiences. Images depicting the situations being described provide an unfiltered look into their circumstances from their point of view. The soft color palette and fluid transitions reflect their heartfelt testimony, capturing each event with intimacy and candor.

What are you working on now?

‘Undertow’ is a documentary animation that explores and visualizes personal experiences of anxiety, depression, and anger through the medium of painting-on-glass animation. Using recorded interviews, I interviewed several people about their experiences with these conditions and asked them how it felt, what it looked like, and how it affected them.. These testimonies serve as the foundation for the abstract painted animation.

Using an analogue painting-on-glass technique, I will animate abstract forms that visualize the testimonies. The fluid nature of this medium allows for spontaneous expression, capturing the internal turbulence and emotional intensity described by the interviewees.

CM: Would you do another long-form animated film?

SS: I don’t want to do another hour-long film again, but of course never say never. At this point shorts are more manageable, but it depends on the material. With ‘Truth Has Fallen’ I felt it had to be longer to get the information that needed to be in there. So, it depends on the quality of the information I get and if I can make it work in a short film, or if it needs to be extended.

CM: Do you teach documentary and animation to your students?

SS: I have been teaching a Documentary Animation Production class since 2010. In this class we study documentary animation films made around the world and the students collaborate on a film. I then enter the finished films in film festivals. Some of them have done very well – you can view the films here.

When I’ve taught production courses before they’ve been more of a studio model where you’d had one director, an animator, a designer, etc. But the way I’ve taught this class is that everybody is an independent filmmaker so every single student is the director. It invites chaos, but at the same time each student gets to try every single step of production, from choosing the story to transcribing and editing, and the actual animation. So they all have to participate in every part of production.

CM: Do you feel that documentary animation is picking up momentum?

SS: I really do. I think there’s just a bigger desire for social justice and activism in general, so I think that probably has something to do with it too. When I was giving a workshop in Colombia, they were excited about animated documentary because it was dangerous for them to do live action documentaries, but animation was a way for them to express themselves in a safe environment. As far an animated documentary here in the US, I think it’s a way to use your art to express yourself and I think people who are animators are drawn towards non-fiction to express themselves. As artists and filmmakers and animators we want to be able to use our craft to express ourselves and make something that’s about something. Not that fiction can’t be, but I think documentary… there are so many voices that need to be heard.

CM: In terms of the other work that you see, have you noticed there being changes in animated documentary trends?

SS: I do see more varied techniques such as stop-motion and CG. I’ve seen much more cutting-edge experimental documentary. People are pushing boundaries more and more. Animation can affect you in a different kind of way – where the imagery is so powerful that it kind of shakes you up.

CM: Animators take a different approach to documentary storytelling.

SS: And there is value in both. When I was at CalArts experimental animation, they didn’t really tell you HOW to do things, you operated more in a vacuum, but in some ways I think that’s better. When you don’t know what the rules are you invent your own rules, and you can be much more creative – you can fail but you can also hit the truth in extraordinary ways that wouldn’t have been possible if you confined yourself in a box. So I think that it’s exciting, especially when you see films from countries that don’t support filmmaking in general – people inventing it themselves, and creating their own language.

___

‘Truth Has Fallen’ can be watched in full here. You can find out more about Sheila M Sofian’s work on her website.

Interview by Carla MacKinnon.